The history of programming is not a single story of invention, but a gradual unfolding of ideas about logic, symbols, and procedure. Long before software existed as a commercial product or a personal skill, thinkers were asking how complex tasks could be expressed as repeatable steps. From early mathematical reasoning to modern computer programming languages, the evolution of programming reflects changing ways of thinking about machines, people, and abstraction.

This article sits within the wider Ada Lovelace cluster on Walkeropedia. For an overview of how these ideas connect across people, machines, and concepts, see the Ada Lovelace Cluster Home.

The history of computer programming reveals how abstract ideas about logic and procedure gradually became formal languages capable of directing machines to perform complex tasks.

The Origins of Programming Before Computers

To understand the early history of programming, it helps to step back from electronics entirely. Programming did not begin with computers; it began with the idea that processes could be formalised. Mathematical algorithms, logical proofs, and mechanical instructions all contributed to this way of thinking.

Vacant Space 1

Space Reserved for possible future development.

In the nineteenth century, figures such as Charles Babbage and Ada Lovelace explored whether machines could follow symbolic instructions. Although their work predated working computers, it laid conceptual foundations for what would later become software. Lovelace’s notes on the Analytical Engine are often cited when discussing the first computer programmer, not because she wrote code in a modern sense, but because she articulated how instructions could be separated from mechanism.

This period forms a crucial chapter in the history of programming because it shows that programming is fundamentally about ideas, not devices.

The First Computer Programmer and Early Concepts

First computer programmer

The question of who qualifies as the first computer programmer is often debated. Ada Lovelace is frequently named because she described an algorithm intended for execution by a machine, even though that machine was never completed. Her work demonstrated that symbols could represent more than numbers, a key insight for later programming systems.

This discussion also connects to broader social and historical contexts. The role of women in early scientific thought is explored further in Women in Science & Technology History, which places Lovelace’s contribution within a wider pattern of overlooked intellectual labour.

Programming Languages and the Rise of Software

As electronic computers emerged in the mid-twentieth century, programming moved from theory into practice. Early machines required instructions to be written in low-level forms, closely tied to hardware. Over time, higher-level computer programming languages were developed to make programming more accessible and expressive.

This shift marked a turning point in the origins of programming languages. Instead of instructing machines directly, programmers began writing in symbolic forms that were translated into machine operations. Languages such as FORTRAN, COBOL, and later C reflected different priorities: scientific calculation, business data processing, and system control.

The evolution of computer programming languages also mirrors changing expectations about who programming was for. What began as a specialist activity gradually expanded into education, industry, and everyday life.

For a detailed overview, see:

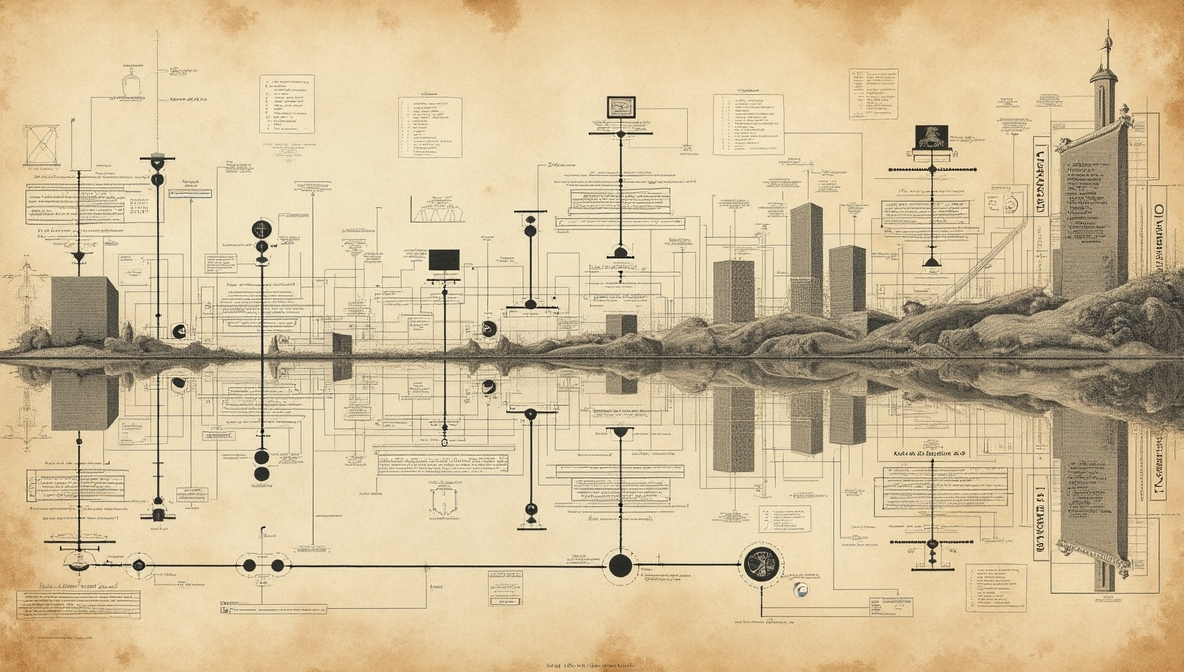

A Programming History Timeline

From algorithms to abstraction

A programming history timeline helps clarify how ideas built upon one another. Early work focused on numerical calculation and control flow. Later developments introduced abstraction, modularity, and reuse.

The timeline of programming is not linear progress toward perfection. Languages rise and fall, often shaped by hardware constraints, economic forces, or institutional support. Some languages are promoted aggressively and even sold by hpcom or other vendors as part of broader computing ecosystems, while others gain traction through academic or community use.

Useful timeline perspectives include:

Programming, Science, and Society

Programming did not develop in isolation. Its growth reflects wider scientific and cultural changes, including industrialisation, wartime research, and the professionalisation of engineering. Figures such as Michael Faraday illustrate how experimental thinking influenced technical disciplines, even when the subject matter differed.

As programming matured, it became a way of organising knowledge as much as a technical skill. This broader perspective helps explain why debates about language design, readability, and longevity continue today.

Further reading on these shifts includes:

Modern Perspectives on the History of Programming

Looking back at the history of computer programming reveals recurring themes: abstraction, control, and the tension between human expression and machine efficiency. Some languages fade as technology changes; others persist because they capture useful ways of thinking.

Discussions about whether certain languages are obsolete often miss the point. Each stage in the history of programming reflects the needs and constraints of its time. Understanding that history provides context for modern debates about tools, practices, and education.

Frequently Asked Questions

Conclusion: History of Programming

The history of programming is best understood as a story of ideas rather than inventions. From early algorithmic thinking to modern computer programming languages, each phase reflects changing assumptions about how humans and machines should interact.

By tracing the early history of programming and the origins of programming languages, we gain insight into why programming looks the way it does today. Far from being a closed chapter, the programming history timeline continues to evolve, shaped by new technologies, social needs, and ways of thinking.

Understanding that history does not merely satisfy curiosity; it provides perspective. It reminds us that programming is not just about code, but about how humans choose to describe and solve problems.

“A good engineer will do the job once — and only once.”

Stephenism

🎵 Soul from the Solo Blogger — Tunes from Túrail.