The story of the analytical engine is not merely a tale of gears, levers, and brass components. It is the story of an idea that arrived long before the world possessed the tools to realise it. Conceived in the early nineteenth century, the analytical engine represents the moment when mathematics, logic, and imagination converged to suggest something entirely new: a machine that could be programmed to carry out complex operations according to abstract rules.

Although never completed in physical form, the analytical engine occupies a central place in the history of computing. Its design anticipated many of the principles that underpin modern computers, from stored data and conditional logic to repeatable instructions. To understand the analytical engine is to glimpse the conceptual foundations of computation itself.

This article forms part of the wider Ada Lovelace cluster on Walkeropedia, which explores the machines, ideas, people, and historical context that shaped early computing. For an overview of how these elements fit together, see the Ada Lovelace Cluster Home.

The Analytical Engine in Historical Context

When historians discuss the analytical engine, they are referring to a design developed by Charles Babbage from the late 1830s onwards. Babbage was already well known for his work on the Difference Engine, a specialised mechanical calculator intended to produce accurate mathematical tables. That earlier machine relied on a fixed method—using finite differences—to generate results.

Vacant Space 1

Space Reserved for possible future development.

The analytical engine went much further. It was conceived as a general computing machine, capable of performing different kinds of calculations depending on the instructions it was given. In this sense, it marked a decisive break from earlier devices, which were limited to single, predefined tasks.

The contrast between the two projects is crucial. The Difference Engine was a calculator, albeit a highly sophisticated one, rooted in a single mathematical method. The analytical engine, by contrast, was designed to follow sequences of operations—what we would now call programs. Where the difference engine calculated, the analytical engine processed.

This distinction places the analytical engine at a pivotal point in the early history of computation, linking mechanical calculation with abstract reasoning.

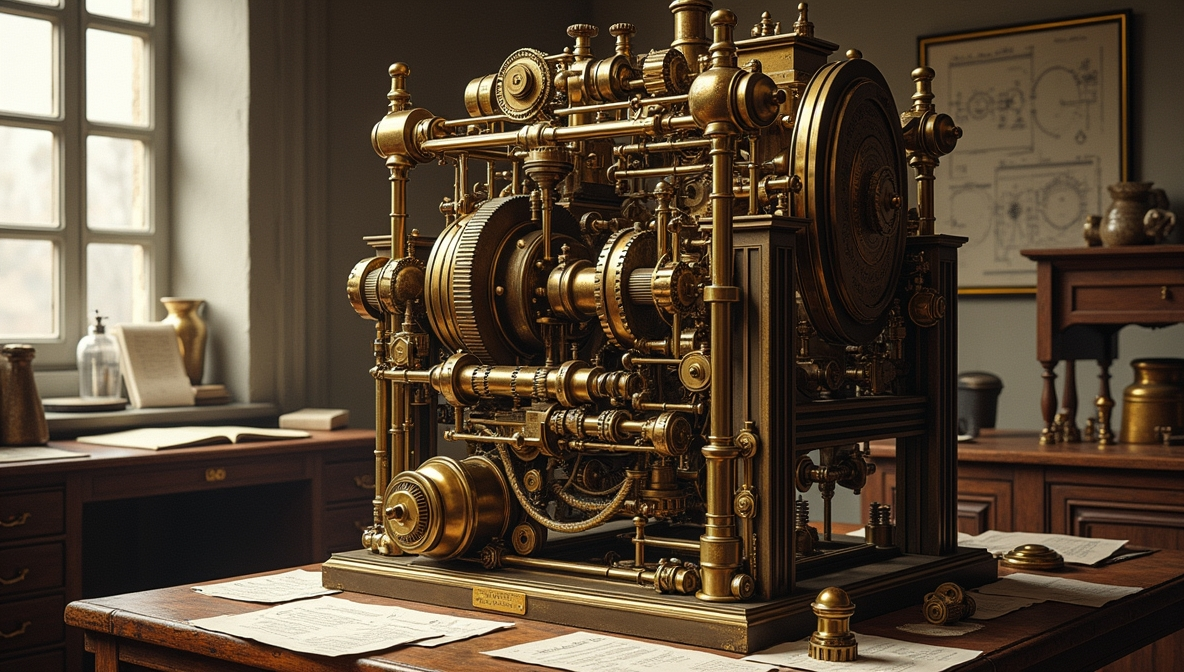

Design and Structure of the Analytical Engine

At the heart of the analytical engine design was a clear separation of functions, an idea that remains fundamental to modern computing. Babbage described four principal components:

- The Mill, responsible for carrying out arithmetic operations

- The Store, where numbers could be held and retrieved

- The Reader, which used punched cards to provide instructions and data

- The Printer, which recorded the results

Together, these elements formed what we might reasonably describe as an analytical engine computing machine, even by contemporary standards.

The punched cards were particularly significant. Borrowed from the Jacquard loom, they allowed instructions to be altered without rebuilding the machine. This meant that the analytical engine design was inherently flexible: the same machine could be used for different problems simply by changing the cards.

Babbage’s plans also included mechanisms for conditional branching and repetition. These features allowed the machine to make decisions based on intermediate results and to repeat sequences of operations—capabilities that align closely with modern notions of control flow in programming.

For further insight into Babbage’s broader vision and engineering ambitions, see Charles Babbage – The Visionary Engineer.

Ada Lovelace and the Concept of Programmability

While Charles Babbage provided the mechanical vision, it was Ada Lovelace who articulated many of the analytical engine’s deeper implications. In her famous notes on the engine—written as an extended commentary on an Italian paper by Luigi Menabrea—Lovelace explored how the machine might operate in practice.

It was here that analytical engine history took a decisive conceptual turn. Lovelace recognised that the machine’s operations were not limited to numbers as quantities. Instead, she observed that numbers could represent symbols, and that the engine might manipulate those symbols according to formal rules.

In modern terms, Lady Lovelace recognised the potential for the machine to operate on abstract representations. This insight anticipated what we now call symbolic processing, a foundational idea in computer science. Her notes included a detailed example—often referred to as an algorithm—showing how the machine might calculate a sequence of Bernoulli numbers.

Importantly, this was not simply a mathematical exercise. It was a demonstration of how a sequence of operations could be encoded, executed, and reused. For a deeper exploration of this idea, see Symbolic Processing: Lovelace and Babbage.

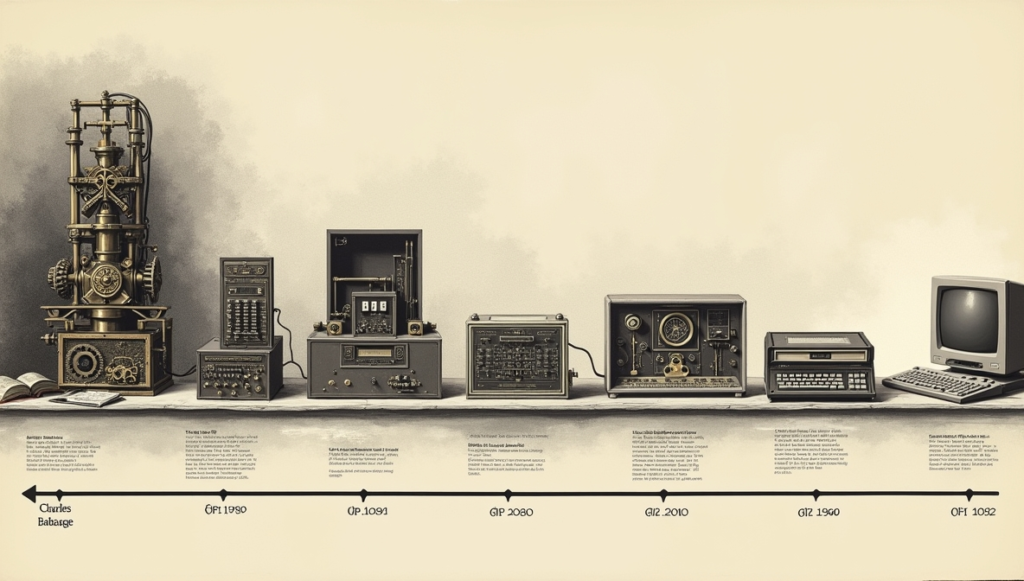

From Difference Engine to Universal Machine

Understanding the analytical engine also requires revisiting the limitations of earlier machines. The Difference Engine, impressive though it was, could only follow a single method. In effect, it was a purpose-built calculator—a decimal difference machine designed to eliminate human error in table production.

The analytical engine was different. Where the difference engine followed one path, the machine could follow many. Where the former embodied a fixed procedure, the latter embodied a framework for procedures.

This shift—from a single calculating process to a general system of instructions—marks the true conceptual advance. It explains why the machine is so often discussed in relation to the broader early history of programming, even though it predated electronic computers by a century.

Why the Analytical Engine Was Never Built

Despite its elegance on paper, the analytical engine was never completed. Several factors contributed to this outcome.

First, the engineering challenges were immense. The precision required to manufacture thousands of interacting mechanical parts exceeded the capabilities of Victorian workshops. Second, funding was inconsistent. Babbage’s relationship with government backers deteriorated over time, particularly after earlier disappointments with the Difference Engine.

Finally, the project was simply ahead of its time. The intellectual leap embodied in the machine design had no immediate practical application that justified the cost and complexity. As a result, the idea remained largely theoretical.

The scientific culture of the period—explored further in Victorian Science & Society and 19th-Century Science—was not yet ready to support such an abstract endeavour.

Legacy and Influence

Although unbuilt, the analytical engine left a lasting legacy. It influenced later thinkers by demonstrating that machines could, in principle, follow formal instructions independent of any single task. This idea underpins much of what followed in logic, algorithms, and computing theory.

Connections can be traced from Babbage and Lovelace to later figures working in logic and formal systems, explored in Logic and Algorithms: From Babbage to Lovelace. The broader social networks of Victorian science, including experimentalists such as Michael Faraday, also formed part of the intellectual environment in which these ideas circulated.

The machine thus occupies a unique position: a machine that existed primarily as an idea, yet one that continues to shape how we understand computation.

For a concise technical overview of the engine itself, see the Encyclopaedia Britannica entry on the Analytical Engine.

Frequently Asked Questions

Conclusion

The enduring significance of the analytical engine lies not in what it achieved in practice, but in what it revealed in theory. Long before electronic circuits or stored programs became feasible, this ambitious concept demonstrated that calculation could be separated from mechanism and governed instead by abstract instructions. In this sense, the analytical engine stands as a bridge between mechanical ingenuity and modern computational thought.

Viewed as an analytical engine computing machine, the design anticipated many principles that would only be realised much later, including conditional logic, repeatable operations, and symbolic manipulation. These ideas were embedded in the analytical engine design, which treated computation as a process rather than a single task. That conceptual shift marked a decisive moment in the development of programmable systems.

Understanding the analytical engine history also highlights the importance of collaboration between engineering and imagination. Charles Babbage provided the structural vision, while Ada Lovelace articulated the broader implications of what such a machine might become. Together, their work reminds us that progress in computing has always depended as much on ideas as on technology itself.

“True engineers are lazy good-for-nothings — because they design once, and let the system do the rest.”

Stephenism

🎵 Soul from the Solo Blogger — Tunes from Túrail.